| The 1732 Voyage of the Pink "John & William"

|

|

|

The Pink "John and William"

and Captain Tymperton

in

The 1732 Immigrants Voyage

By Rick Bushong

April 2014

Revised: December, 2017

|

The Dort packet boat from Rotterdam becalmed.

Painted 1818 by Joseph M. W. Turner, (with liberties).

|

|

|

On the west bank of the Philadelphia Harbor in 1732, a small ship, named "John and William" finally pulled alongside the docks and cast its lines. 1; 2 It was very late. Out of the eleven ships bringing immigrants to Pennsylvania that season, it was the last to arrive.2 The date it docked was Friday, October 17, 1732, which was the same day the men, who were its passenger, were taken to the Philadelphia City Hall. All the foreign-born men were required to swear their allegiance to King George II and England.2 The ship's captain, Constable William Tymperton, and some of his sailors had probably, herded the men onto the dock and escorted them to City Hall, a few blocks away.3 As usual, Philadelphians gathered around, to look for family, or to gawk in curiosity at the new arrivals. Others were looking for strong new workers or servants that they hoped to buy when the shipping company indentured or sold-off insolvent passengers. But that fall day, they would have seen, only gaunt and sickly men, wearing near rags. After the deprivations of their long and harrowing journey, the men could barely walk.3

These now bedraggled immigrants had boarded the boat, in Rotterdam, Holland, over five months earlier, in the spring. Sometime in May, the "John and William" departed Rotterdam and sailed, to Dover, England. Then around June 20th, it began the transatlantic crossing, which turned into 17 grueling weeks at sea, before the survivors set foot in America. But Rotterdam and the deadly voyage to America had not been the beginning of their sojourn. For most, it had started months before.3

The majority were Protestant, either German or descended from Germanic families in Switzerland, the German-Swiss. Originally most relocated to the Palatinate, also known as German Pfalz. They historically were the lands of Count Palatine, and they lie mostly in Southwestern Germany.

The area occupies more than a quarter of the contemporary German-federal state of Rhineland-Palatinate.4

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Catholic Church began systematic and relentless persecution of most sects of the Protestant faith, and the results were thousands of refugees and large migrations into the Palatinate region. While in the Palatinate, they gained some safety from Catholic antagonism, but yet lacked total freedom, such as the right, in many places, to own land. Then as boundaries in the area varied with the political and dynastic fortunes of the day, even that security disappeared. In the face of the religious and often Royal oppression, the only way they could stay true to their differing Protestant beliefs was to leave. For many, the only choices were new territories, promising religious freedom, in English domains. Most immigrated to William Penn's land of Pennsylvania, but some also ended up in New York, Massachusetts, and North Carolina as well as other British territories in the Caribbean.5

|

|

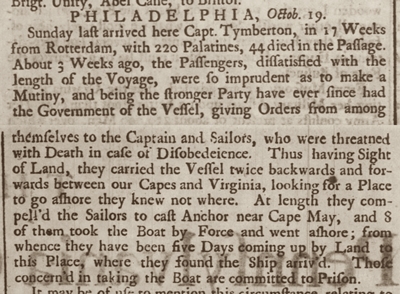

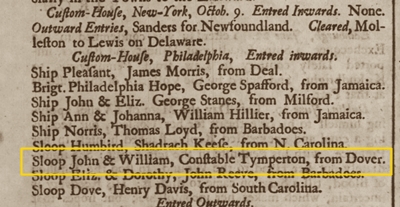

The Pennsylvania Gazette, Oct. 9-19, 1732, page 2

"Sunday last arrived here Capt. Tymberton, in 17 weeks from Rotterdam, with 220 Palatines, 44 died in the Passage. About three weeks ago, the Passengers, dissatisfied with the length of the voyage, were so imprudent as to make a Mutiny, and being the stronger Party have ever since had the Government of the Vessel, giving Orders from among themselves to the Captain and Sailors, who were threatened with Death in case of Disobedience. Thus having Sight of Land, they carried the Vessel twice backwards and forwards between our Capes and Virginia, looking for a place to go ashore they knew not where. At length they compelled the Sailors to cast Anchor near Cape May, and eight of them took the Boat by force and went ashore from whence they have been five Days coming up by Land to this place, where they found the Ship arrived. Those concerned in taking the Boat are committed to Prison."6

The Pennsylvania Gazette, Oct. 9-19, 1732, page 2

Custom House (No. 203), Philadelphia

The Pennsylvania Gazette, Oct. 9-19, 1732, page 2

Custom House (No. 203), Philadelphia

Entered Inwards Sloop John & William

Constable Tymperton, From Dover.6

To read the full page click here.

|

|

Traveling to Rotterdam on the Rhine River,

a trip that took several weeks.

|

|

So as had been happening for years, when the first thaws of spring came, Swiss-German Palatinates began a daunting journey to the New World, for the chance to be free from oppression and the hopes of owning land in William Penn's Country. Usually, through the years, a few hundred Palatinate refugees began the journey, but in the year 1732, many more came.3 Like those before them, their odyssey would cost much, if not all their money. For some, it would cost their freedom in years of servitude, paying for passage. Some would pay with their lives.

From Pfalz, their journey began when the families or small groups left their homes and traveled to the river Rhine. Arriving, they loaded all their possessions and family onto one of the multitudes of barges and small boats that plied the river. For the next four to maybe six weeks, they would float down the Rhine, hundreds of miles, to Rotterdam, Holland.3 Between 1727 and 1775, the city and port of Rotterdam was the main point of departure for roughly 90 percent of the German immigrants traveling to America.

One of the reasons the trip down the Rhine took so long was that the boats could pass as many as 36 various Custom Houses. Each custom house represented one of the countries, or the many jurisdictions and fiefdoms. Each had officials who examined the cargo and boats then exacted their fees, all at their leisure.3 Floating along on the ancient waterway, the Middle Rhine slopes are lined, with centuries-old, stone forts and castles.3 There are as many as 40 peering down from above, each guarding their section of the river.7 For our immigrants, riding silently on the currents below, the ancient battlements could have served as stark reminders, that the land they were leaving had been embattled for hundreds of years. Either at war or constantly under siege.

|

Arriving in Rotterdam, now homeless refugees, they ended up in large refugee camps outside of the city.

The city, in the past, had been so overrun with the German refugees, they eventually forbid them from entering. So Palatinates stayed in tent camps outside. There, it could take five or six weeks to find a boat.8; 9 All the while, they had to live on their food and money, or the help of local charities.

For a few years, until that season, the Dutch Reformed Synod of South Holland, as well as the Dutch Mennonites, sympathetic to their brethren's plight, had been helping the refugees by providing food, medicine, and even money.10

That may have been a cause for the big surge of German emigrants in 1732. That even though December 31, 1731, the Christian Synods discontinued sending money. They stopped because that year, they were embezzled out of 2,079 Guilders, by church Elder, Jacob Reif, who had been intrusted, with delivering the money to Pennsylvania.11

"the Christian Synods have resolved to send no more donations to Pennsylvania, until Do. Weis and the Rev. Consistory (Rev. van Ostade) of Philadelphia shall have sent hither only a report that the money already given was actually received, but also a proper specification for what it was spent."11

The Dutch Mennonite Church continued helping, until they too, were overwhelmed. The multitudes of refugees all reported they were fleeing "hard usage, intolerable servitude, and religious grievances". 12 It seems likely, that the numbers, who ended up descending on Rotterdam, swelled that year, as a result of the two church's support. The results were that over 2,000 refugees, of all religious persuasions, came to Rotterdam.2 Later, after the last refugees had sailed to the new country, the Mennonite Committee announced they were also ending their support for the migration. They passed the resolution in July 1732, that they would no more help the Palatines travel, for any reason whatsoever, except for return fare.12; 13 It apparently worked and the exodus dropped to its former levels for the next few years.14

|

|

I am at Rotterdam, engraving by William Miller after Birbet Foster. Over 90% of the Colonial American Immigrants, coming to Philadelphia, came through Rotterdam.

|

But regardless, it was to be the largest migration to the new world yet. In 1732, the number of ships needed for the transatlantic crossing jumped, from four ships, with 600 immigrants, the prior year, to eleven. In the end, 2095 men, women and children, were listed immigrating. They were listed on the passenger manifests and would have paid a fare. Then, consider children under five and uncounted, many more emigrated that year. As a record, it stood unbroken until 1738, when immigrants reached 3,314.14

|

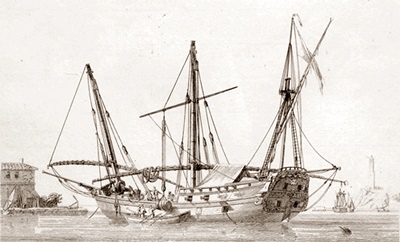

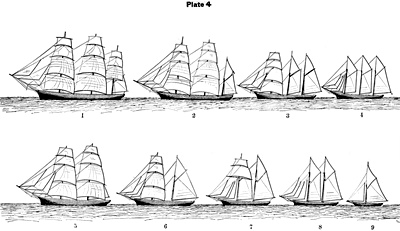

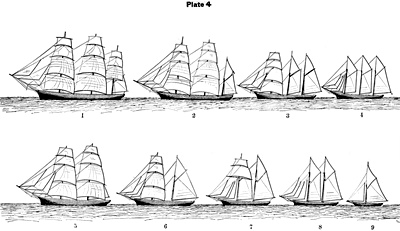

A classic Pink loads cargo. This rendering is possibly the closest, yet found, to the Pink "John and William."

|

|

In the summer of 1732, with the unexpected crush of refugees, there were several thousand waiting and suffering in the tent camps on the outskirts of Rotterdam. Ships that could carry them to Pennsylvania, were desperately needed. Of those rushed into service, one of smallest vessels, was the enigmatic Pink "John and William," of Sunderland, whose Master and Captain was Constable William Tymperton.2; 15; 16

From the few records of the ship, just a handful of written accounts, a lot can still be determined. Also from a study of accounts of other ships. She was called a "pink" by her master, Tymperton as well as in other accounts.2 The term "pink" is from the Dutch word "pincke" which translates to "pinched." A pink is described as any small ship with a narrow or "pinched" stern that usually had a flat bottom with a shallow draft. They had a large cargo capacity, but until then, were not usually used for transatlantic transportation.17 The "John and William" is one of only five "Pinks" ever used for the migration, in 1732 and 1733.2

|

Later, when the "John and William" entered the harbor in Philadelphia, she was called a "Sloop", by the Harbor Master. He was referring to her size and rigging, or in other words, her sails.6 A sloop is described as a smaller boat with a single mast and a rig fore and aft. They never have more than one headsail.18; 19; 20 The size and tonnage of the "John and William," was never stated, but it can be estimated, from a study made of 16 different period ships involved in bringing immigrants to Philadelphia. Its findings:

"the smallest was 63 feet long (over the gun deck), 20 feet 11 inches breadth of beam and 9 feet 7 1/2 inches as the depth of hold, with a tonnage of 108 73/94 tons. The largest ship was 99 feet 8 inches as length of deck, 26 feet 5 inches as breadth of beam and a tonnage of 311 16/94 tons. The average tonnage was 178 tons."21

Charts and descriptions indicate the "John and William" would come closest to the smallest, 63 feet. Also, we can get an understanding of the general crew sizes from another ship, as seen in an advertisement published in the Pennsylvania Gazette, October 15, 1747.22 It lists the Ship "Two Brothers", which is much larger, weighing 250 tons, as having a crew of 14, (as well as 14 guns).

From this, the "John and William" had only the one mainsail. She was likely built, in Holland, in the Dutch, pinched-stern style, with a flatter bottom and hence a shallow draft. Probably somewhere under 70 feet in length with a gross tonnage of possibly 110 tons, as in the illustration (above), she may have had a few guns for protection. Her crew would have consisted of maybe ten or so sailors, plus her Captain. As such, the "John and William" was probably one of the smallest boats used to transport Palatinates to Pennsylvania, and certainly not the fastest.

|

|

On this 1834 chart, the sloop is the smallest boat - #9. The "John and William" was somewhat larger when compared with this illustration, but had the same sail configuration.

- The Ship - Three masted, square rigged on all three masts.

- The Barque or Bark - Three masted, square rigged fore and main, fore and aft rig on mizzen.

- The Barkentine - Three masted, square rigged fore, fore and aft rig main and mizzen.

- The Schooner - Three masted or four masted fore and aft rig.

- The Brig - Two masted, square rigged.

- The Brigantine - Same as brig but without a square mainsail.

- The Hermaphrodite Brig - Two masted, square rigged fore, fore and aft rig main.

- The Topsail Schooner - Two masted, square rigged forward, but with a fore and aft foresail.

- The Schooner - Two masted fore and aft rig.

- The Sloop - One masted, fore and aft rig.

Note: A vessel is said to be square rigged on a certain mast, when the sails set on that mast are bent to yards, and fore and aft rigged when the sails are bent to gaffs. Source: Text-Book of Seamanship, Published 1834, 18

|

The ship's English Captain was Constable William Tymperton, who had been born in 1690, likely in London.15; 16 At the age of 42, and given the seriousness of a transatlantic crossing, especially with passengers, he had probably been sailing for several years. But this crossing to Philadelphia, carrying immigrants, was his first, and it was to be his last.2 That year's influx of refugees offered shipping companies a tantalizing opportunity. The "John and William's" owners and her Captain were well aware of how much more money there was in hauling human cargo, instead of their usual freight.

How much could the voyage make for the shipping company? Well if they charged in 1732, close to what author and voyager, Gottlieb Mittelberger's 1750 - 1754 prices were, it would have been £10 (10 Pounds Sterling) or 60 Gold Florins.3 To put this in perspective, £10 in 1732 adjusted for inflation, would equal $2,177 today. If close to 169 passengers paid full fare, it could be over $300,000. On the other hand, it they had paid in Gold Florins, each Florin contains about 3.5 grams of gold or 210 grams per passenger. This would total 3.18 pounds of gold which is equal to well over $1,000,000 in our day and age.

|

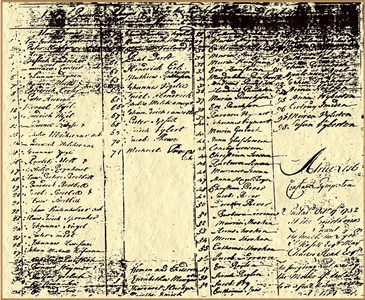

The Pink "John and William" passenger manifest.

|

|

According to the Pennsylvania Gazette, 220 refugees were to become passengers on the "John and William."6 But this figure is inaccurate because only paying passengers counted. In one example, the Weisel (Wysel/Wisel) family had four children with them who were not counted or listed, so there were more. Most of the passengers probably had to spend several weeks in the camps, waiting for ships to arrive in port, to be outfitted, and readied to sail.3 It was in late May or early June, that the "John and William" docked in Rotterdam and began taking on cargo, food, water, and passengers. The refugees, as individuals or in small groups, met with Master Tymperton, where they agreed on a price for passage and the transport of any freight or belongings they may have had.

They then gathered their families and belongings, and went down to the docks to begin loading in preparation for the journey. They would have used the opportunity to buy any food and medicine they could afford before boarding the boat. Easily, when boarding, more than a few were aghast at how small the boat was. They might have wondered if they would have been better off making their journey, the prior year, as several different families' immigration spanned the two seasons.2; 32. The passengers found themselves in the steerage compartment and any other space they could fit. But ultimately, over 220 men, woman, children, and their belongings, along with any other cargo, were crowded into one of the smallest boats to carry immigrants to Colonial Pennsylvania.24

|

|

Nationally, the "John and William's" passengers were a mixture of German, German-Swiss, and French, with most hailing from Pfalz. Though there were a couple of Catholic and maybe even Jewish passengers, all the rest were Protestants, Reformed and Mennonite, mixed, with the majority belonging to the Reformed sect.2 It is not known if the crew had a chance to build bedsteads or if there even was room, but as crowded as the small boat was, probably most slept on the floor. Once a passenger boarded the "John and William," their suffering began in small dark quarters with limited use of the deck, including while the boat was in the harbor. As they arrived, passengers were added to the others, already in the confines of the vessel, while the crew continued stowing freight. Even, after all, was ready, the ship and Captain Tymperton still had to wait for the tides and the winds. It could have taken up to a couple of weeks, waiting for the winds, before the "John and William" finally got underway, on the next part of their odyssey, England.2

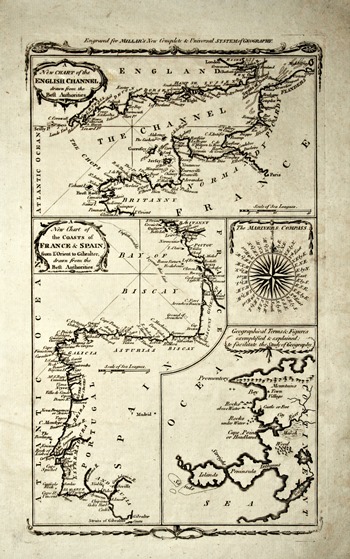

From Rotterdam, the "John and William" sailed 230 miles (370 Km) south, through the Straits of Dover and to the English Channel, and anchored in Dover, in Kent, England. The ships always made a last stop in an English port, for the foreign-born passengers to receive clearance to emigrate to the Pennsylvania Colony. Most of the ships anchored farther on, at Cowes on the Isle of Wight, but there were seven other ports along the English channel that were used.2; 3; 32 The journey to England could take anywhere from two to four weeks. Once underway, the passengers, who had already been stuck on board for sometime, became even more miserable. In the dark and confined quarters, almost as soon as the ship started moving, many became seasick, and the near constant smell of vomit was added to burden of the refugees. Arriving in Dover, the "John and William" could have been delayed for as long as two weeks clearing British customs, taking on food and cargo, and waiting for favorable winds.25 All the while the passengers were virtually trapped while the boat was anchored offshore.3; 25

|

|

A Map of the English Channel, (top portion). The "John and William's" transatlantic crossing began from Dover, seen in the top right hand corner.

|

|

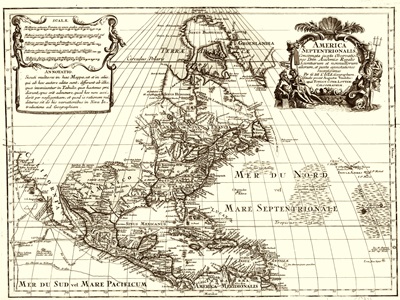

A 1733 map of the American Coast.

|

|

Around June 20th, the winds were right, Captain Tymperton gave orders to weigh the anchor and set the sails, and the "John and William" sailed out of Dover. The Captain piloted her through the English Channel and around the southern tip of England. Along the way, they passed the Isle of Wight and the other ports, lining the English coast. At length, they left the relative security of the English Channel and headed into the open Atlantic, where the real torment and terror began. The "John and William," with her cargo of 220 hopeful immigrants, were bound for Pennsylvania. It was the final leg of their odyssey and was the hardest. The voyage, from Dover, on the open ocean, was more than 3500 miles (5633 kilometers) and would last 17 weeks. Twenty percent of them would die. Those who survived endured starvation, thirst, and a mutiny among innumerable hardships.2; 26

On the voyage, the immigrants stayed below, as there was little room for them on the small upper deck. So even when the weather was nice, they remained virtually trapped in the dark, squalid confines of the lower-decks. Gottlieb Mittelberger's description of his 1750 crossing in the "Osgood", which was a larger ship, offers a vivid and realistic account of what the experience.3

|

"During the journey the ship is full of pitiful signs of distress – smells, fumes, horrors, vomiting, various kinds of sea sickness, fever, dysentery, headaches, heat, constipation, boils, scurvy, cancer, mouth-rot, and similar afflictions, all of them caused by the age and the highly-salted state of the food, especially of the meat, as well as by the very bad and filthy water, which bring about the miserable destruction and death of many. Add to all that shortage of food, hunger, thirst, frost, heat, dampness, fear, misery, vexations, and lamentations as well as other troubles. Thus, for example, there are so many lice, especially on the sick people that they have to be scraped off the bodies. All this misery reaches its climax when in addition to everything else one must also suffer through two or three days and nights of storm, with everyone convinced that the ship with all aboard is bound to sink. In such misery all the people on board pray and cry pitifully together."

Source: Journey to Pennsylvania in the Year 1750 and Return to Germany in the Year 1754, by Gottlieb Mittelberger, Published 1756.

3 |

|

Mittelberger stated his crossing took around 15 weeks, but the "Osgood" arrived on September 29, 1750, versus his stated, October 10th, and it may have been closer to 13 weeks. Most of the 324 ships carrying Colonial immigrants to Philadelphia, took somewhere between 8 to 12 weeks, and the shipping companies, as well as passengers, planned for a voyage of that duration.3 But the "John and William" took 17 weeks. It is understandable, as the voyage stretched on, that Captain Tymperton would have had to reduce the already meager rations of food and water, again and again, to keep from running out. Usually, the only food left for passengers later was "old and sharply salted food and meat, with foul water."3 Any food the passengers had brought, would likely have been eaten, or rotted long before.3 Now as the journey stretched out past 10, then 12 weeks and longer, more than hunger, the reality of starvation became a serious concern.

Of course, it was the weaker passengers and children who were most likely to die. On this voyage, they succumbed at an average of about one every three days, but now after the many weeks with little food or water, it was likely one or so every day. The children were given so little a chance by the shipping companies, that they did not charge for those less than five years old, if they were to survive.3

|

|

A Ship is tossed at sea. The "John and William" was much smaller with only one main mast.

|

As they died, the children's bodies and those that would fit were dropped out the port holes into the Atlantic. The larger or adult bodies were taken topside and dropped from there.3; 32 In their extreme hunger, even ships rats and mice, would be caught and eaten. On one voyage, rats reportedly sold for a shilling sixpence and mice for sixpence each, when available.25 But when weeks dragged on and on, and the torment from hunger and suffering grew, some of the passengers could no longer stand it, they captured and took over the ship and mutinied.

|

A mutiny in a different time and different place.

|

|

The passenger mutiny of the "John and William" occurred at the end of September 1732, after fourteen weeks sailing from Dover. The Pennsylvania Gazette, Ben Franklin reporting, said that eight passengers took over the ship and were all imprisoned later.6 But there are no known eye witness accounts of why they mutinied and who the mutineers were. Clearly, the length of their journey was the cause. But what drove the men to such a desperate act was overpowering thirst and hunger. Perhaps, bad luck or bad weather could be to blame for the slow passage. But a likely factor was leaving England from Dover, which was the first port Capt. Tymperton saw after leaving Rotterdam. That added time and made the transatlantic portion of the journey longer from the start. Also significant is recognizing that the "John and William," was one of the smallest ships, with "less sail" to catch the wind, not to mention, she was also fully loaded, if not overloaded.18; 19 Inevitably, these factors all contributed. Some have even suggested that Captain Tymperton went mad and lost control of the vessel, but there is no evidence to support this.

|

There is a single report identifying a mutineer named Abraham Dubo/Duboe/Duboy/Diebo, and admittedly, it is family lore and an unsourced report. It states that he mutinied over money for the price of passage.27 This explanation is baffling, as there is no reason for a Captain to raise the fare or a passenger to ask for a reduction so far into a voyage. But it seems more plausible that if the cause was over money, it was over the price of food. Because until later, when Britain passed passenger regulations, there was a practice on some ships of selling food above the normal or reduced passenger rations. It is possible, as the amount and freshness of the rations of food, and water, were reduced, again and again, the "extra" food became scarcer and hence more expensive. When a passenger or family was out of money, they either starved with the ship's meager, nearly inedible, and reduced rations or borrowed money for food. There were even reports of some ships selling food at cutthroat prices.28 And it was from the shipping company that the starving passengers were borrowing. It was a debt most could only pay with their freedom by becoming indentured.

|

|

The mutineers, after taking over the ship, and filling their stomachs, would have known nothing, about sailing a ship. Ben Franklin reported they were giving orders to the crew and Captain Tymperton, and threatening them with their lives.6 It is not stated but they most likely had guns and weapons, either taken from the crew or their own. But aside from taking charge of any remaining food and water supplies, the only orders they could possibly give would be to "sail on." So the "John and William" continued on in this manner for a week or so, until land was sighted. Captain Tymperton, unfamiliar with the American coast, would have had few maps of the coastline and waters. Concerned for his ship as well as keeping with good naval procedures, he probably began trying to "find the bottom". He would have ordered a crew member to start "sounding for the bottom," by throwing a heavy lead weight, attached to a rope, over the side of the ship to test the depth of the water. If the weight touched bottom at 6 fathoms, then that meant the bottom was only 36 feet down. (One fathom equals six feet.)29

|

|

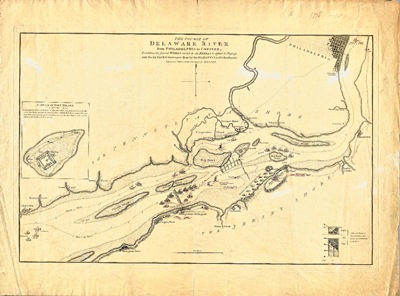

A 1757 map of the Atlantic Coast, showing parts of Pennsylvania, including Philadelphia, as well as, Maryland, Delaware, and New Jersey. |

|

Rowing ashore, in a dory, from a different time.

|

|

With land in sight, their odyssey appeared over. But now, the mutineers realized they would be arrested and imprisoned if they were to sail into Philadelphia Harbor. So as the Pennsylvania Gazette reported, they ordered the Captain to sail south, looking for a place go ashore, where they might have a chance to getaway. It is not sure how far they sailed, but the paper reported they sailed between the Capes, or near Cape May, and the "Virginian territories".6 However far it might have been, it was a hopeless choice, as south along the coastal area is totally desolate. It continues through Delaware, Maryland, and stops in Virginia, at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, and consists of a virtually uninhabited coastal plain that is just flat and sandy areas with very few or no hills.30

It is some 156 miles (136 nautical miles) from the Cape May, or the Delaware Bay Entrance to Chesapeake Bay Entrance, Virginia. The mutineers would have only seen miles of uninviting coast, with no settlements along the way, and understood they would have little chance of surviving. 31 It is doubtful, from the report that they sailed as far as the Chesapeake Bay, but even if they had, the Captain would need to have charts and probably help from a local pilot, if they were to enter it. Over the next week or so, Ben Franklin reported, they made the trip between Cape May and Virginia and back twice, all the while extending the torment of the remaining passengers.6 Still as their desperation grew, there was no place the mutineers thought they could survive. The second time they came upon the capes of the Delaware Bay, they ordered Captain Tymperton to drop anchor. So the "John and William" anchored at the mouth of the Delaware River, which led to Philadelphia.6 From there, they took one of the ship's rowboats, and all rowed to Cape May, on the New Jersey side of the river. Ben Franklin noted they were all arrested as they arrived on foot in Philadelphia, probably in worse shape than before. and that the ship had arrived ahead of them.6

|

In the mean while, back on the ship, with the mutineer's departure, the mutiny was finally over and Captain Tymperton had control of the ship again. The "John and William" was now close to Philadelphia, but still faced a voyage of some 80 miles up the river to Philadelphia Harbor. The river could be a long and hard trip, and winds played a critical part. If the prevailing breeze was coming from the south, then the ship probably reached Philadelphia in short order, similar to Gottlieb Mittelberger's experience. His ship's journey from Delaware Bay was only 40 hours. 3 But other reports are different, John Naas' ship took five days, and publisher, Christopher Saur noted that some ships needed eight to ten days to travel the same distance.1; 32 Captain Tymperton would be completely unfamiliar with the river, and when one or more of the area's river Pilots or Navigators rowed out to the ship and offered their service, Captain Tymperton undoubtedly hired one.32 The Pilot, who was very familiar with the river's currents and area winds, would for a fee, take the helm and sail the ship all the way into Philadelphia Harbor where it would drop anchor and wait for clearance to dock. 1

|

|

A map of the Delaware River from during the Revolutionary War, made in 1778. It was still several days voyage from Delaware Bay to Philadelphia. |

An engraved sketch by George Heap, of Philadelphia viewed from New Jersey depicted as it looked in the 1730s. The numbers identify the various buildings. Number 6 is the Court House.

|

|

Now the "John and William," was off of the unpredictable and often turbulent Atlantic Ocean, on the relatively safe Delaware River, and with an experienced pilot at the helm. The Captain, crew, and passengers all must have been very relieved and excited. As they floated along, towards the end of the odyssey and the beginning of their new lives, passengers reportedly crowded onto the ship's small deck. Just happy to be out from the confines of the cramped quarters, they would only see miles and miles of virgin forests that grew right up to the river's edge. At length, the shoreline began to be occasionally dotted by houses or cabins, and they could tell they were getting closer. Finally, on Sunday, October 12th, a fall day, said to be clear and serene, they sailed into the harbor at Philadelphia.6; 33

The ship took a few days to gain clearance, and during that time, Captain Tymperton had the Passenger Manifest drawn-up to determine who had to pay, and it listed 71 men and 98 women and children, leaving off those under five years old. The sick and starving passengers invariably began getting food and medicine, brought out to the ship in rowboats, probably as had happened in 1733 for the "Pennsylvania Merchant," which was the ship of John Naas, who wrote the letter to his son about the cruise, (to read, click here). Naas was a member of Abraham Dubo's church, they, and inevitably other families as well as charities sent food and medicine by rowboats.32

|

|

On Friday, October 17th, only after the ship was declared free of contagious disease, was it allowed to off-load or tie up to the docks. That day all the healthy men, over 16 years old, were administered the Oath of Allegiance, which was usually given immediately after clearance and docking.3 One by one, passengers paid their debt for the passage, and Captain Tymperton allowed their departure. Those who could not pay their fare and possibly for the food they had on account, were not freed yet. Buyers had to be located for each of them, to pay their debt, and eventually, they were indentured. Their freedom would have to wait because they were to spend the next two to four years in servitude. Those families who had money settled their accounts and had any possessions hauled over the side of the boat, onto the docks. As the immigrants set foot for the first time in their new country, they were ending a daring and stunning sojourn. It had begun in the spring, months before, and at such a cost. But at last, they were finally free from oppression. They had made it to America!

|

But the story continues in The Voyager's Epilogue click here

This

Article is Copyright ©2020 by Rick Bushong and

Commercial Use is Prohibited.

Non-commercial use is

permitted if copyright information is

included.

|

References:

- Life in Mid-Eighteenth Century Pennsylvania By John T. Humphrey

- A collection of upwards of thirty thousand names of German, Swiss, Dutch, French and other immigrants in Pennsylvania from 1727-1776, by Prof. I. Daniel Ruff, 2nd Edition Published 1898, Page 84

- "Journey to Pennsylvania in the Year 1750 and Return to Germany in the Year 1754" By: Gottlieb Mittelberger, Published 1756

- Wikipedia: The Palatinate

- The Brobst Chronicles

- Pennsylvania Gazette, No. 203, Oct. 9-19, 1732, Republished in: Historic background and annals of the Swiss and German pioneer settlers, By Frank Eshlemen, Published 1917, Page 245

- Wikipedia: The Middle Rhine

- Souls for Sale

Two German Redemptioners Come to Revolutionary America,

edited by Susan E. Klepp, Farley Grubb, and Anne Pfaelzer de Ortiz,

Copyright: 2006

- The Ordeal of Early Ship Travel by Our Ancestors

, Submitted by Hugh L. Yoho:

- Historical Notes Relating to the Pennsylvania Reformed Church, Volume 1,

by Henry Sassaman Dotterer, Published 1899, Page 174

- Historical Notes Relating to the Pennsylvania Reformed Church, Volume 1,

by Henry Sassaman Dotterer, Published 1899, Page 191

- Maintaining the Right Fellowship, by John Ruth, Published 2004, Page 109

- Skippack Historical Society

- Marianne Wokeck: The Flow and the Composition of German Immigration to Philadelphia, 1727-1775

- Exposition on Common Prayer, reprinted 1860 in Notes and Queries Page 110

- Exposition on the Common Prayer, February 22 1737, No.XXXII

- Wikipedia: Ship - Pinks

- The Text Book of Seamanship, Copyright, 1834, by D. Von Nostrand, republished 1894 Page 10

- Wikipedia: Sloop

- William Falconer's Dictionary of the Marine, Revision of the 1780 London edition, by Thomas Cadell Page 1227

- The German Immigration into Pennsylvania through the Port of Philadelphia from 1700 to 1775

Part II: The Redemptioners, by Frank Ried Diffenderffer, Published 1900, Page 48 and 50

- Pennsylvania Gazette, October 15, 1747, Page 3

- Guildhall Library Manuscripts: index to St Katharine by the Tower marriage licence records

Tower Marriage Licence Records

- Transcriber's Guild, Pink "John and William" Passenger List

- Pennsylvania Germans, A Persistent Minority. William T. Parsons, 1985, excerpted Pages 47-60

- Distance calculator

- Days Of Yore, by Betty Hamby Gripentog, Published 2013

- The Doric Columns, Emigrant Ships

- The Second Sea Congregation, 1743, Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society, by John C. Brickenstein, Pages 122-123

- Wikipedia: Delmarva Peninsula

- Distances Between United States Ports: Page 9

- The John Naas Letter, of the Crossing on the "Pennsylvania Merchant" 1733

- Notes and Queries: Historical, Biographical and Genealogical,

edited by William Henry Egle, Published 1898 Page 200, Hubley

|

This Article is Copyright ©2020 by Rick Bushong and Commercial Use is Prohibited.

Non-commercial use is allowed if copyright information is included.

|