| The 1732 Voyage on the Pink

"John & William" - Voyager's Epilogue

|

|

|

|

The Pink "John and William"

and Captain Tymperton

in

The 1732 Voyager's Epilogue

By Rick Bushong

April 2014

|

|

|

|

|

|

The "John and William" docked, but the 169 passengers and their children were not immediately free to go. They were required to stay on the ship until Captain Tymperton released them. The men, all being foreign-born nationals, were taken to City Hall to swear allegiance to the British Crown and sign their names or make their mark and were returned to the ship. Then when they had paid for their passage and any other charges that accumulated on the voyage, the passengers were free to go. The rest remained virtual prisoners of the ship and Capt. Tymperton.1; 2 Likely

family, friends, and concerned townspeople

continued to supply food, water, and medicine to the boat,

as they did for the brigantine "Pennsylvania Merchant" in 1733.2 It was worse for those who could not pay their full bill with the shipping company. They had to indenture

themselves to someone who could pay their bill. In return, they would agree to work to satisfy that debt. However, those

looking for servants and able workers would have found it difficult to judge between the malnourished and sickly remaining passengers. Because of this, the sickest had to stay the longest on board the ship.1 Eventually, except for a few delinquent accounts the rest became indentured. Of those, some were in servitude for as little as two years, but others, for example, Henrich Gek (Keck) it was three or four years.40

|

|

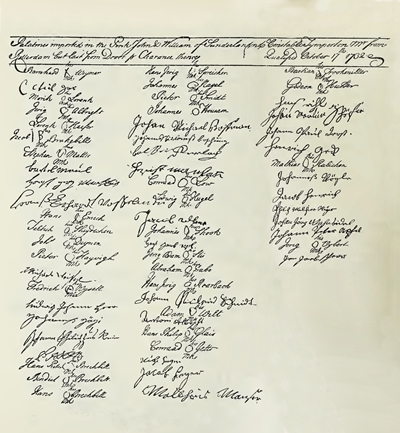

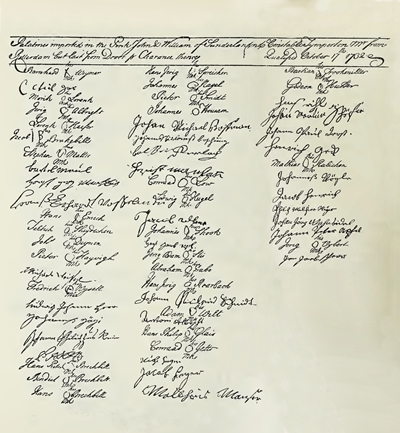

The Pink John and William's" Oath of Allegiance, October 17, 1732. Nicholas' signature is located in the center, sixth from the top and below fellow passenger, Johann Michel Hoffman's similar signature.

|

The Oath

"I do solemnly, sincerely and truly acknowledge,

profess, testify and declare that King George the

Second is the lawful and rightful King of the Realm of

Great Britain and all others his Dominions and

Countries. And do declare that I do believe the Person

pretending to be Prince of Wales during the Life of

late King James hath not any right or title whatsoever

to the Crown of the Realm of Great Britain. I will of

my best endeavors and make known to King George the

Second and his successors all treasons and traitorous

conspiracies which I shall know to be made against

him. And I do make this Recognition, Acknowledgment,

Renunciation and Promise heartily, willingly and

trule."

|

The Men:

1 Hans Earhart Vosselman

2 Pieter Harbyn, sick

3 Hans Emich

4 Helflick Shedeicher

5 Laurence Rosier, sick

6 Johannes Deynen

7 Stephen Matts

8 Fridrich Cooler, sick

9 Pieter Huvigh

10 Michael Wysel

11 Fridrich Wisel

12 Laurence Keiyfer

13 Philip Melchionar, sick

14 Ludwick Melchionar

15 Johannes Yege

16 Bartel Moll

17 Philip Reynhart

18 Hans Pieter Britbill

19 Benedick Britbill

20 Jacob Britbill

21 Hans Britbill

22 Johan Vintenhelver, sick

23 Hand Jerick Spreaker

24 Johannes Nagel

25 Pieter Smidt

26 Johannes Hunsam

27 Johan Michael Hufman

28 Nicholas Paushon

29 Bernard Weymer

30 Balsar Gerloch

31 Christian Low

32 Conraed Low

33 Ludwick Hugel

34 Jacob Weyber

35 Morris Lorrence

36 Johannes Shook

37 Hans Jacob Reyl

38 Jerig Adam Stis

39 Philip Jacob Proops, sick

40 Michael Miller, sick

41 Abraham Dubo

42 Philip Dubo, sick

43 Hans Jerick Roerbach

44 Johan Michael Smit

45 Adam Wilt

46 Gerich Albrecht

47 Antonius Albrecht

48 Hans Woolf Doopel, sick

49 Joseph Houbly, sick

50 Hans Philip Glais

51 Conrad Gets

52 Nicholaus Kooger

53 Jacob Kooger

54 Mathias Menser

55 Bastian Trookmiller

56 Giedon Huffer

57 Hans Reyl

58 Johan Martin Shoppfield

59 Casperrias Vielard

60 Hans Jerich Martin

61 Paul Derst

62 Hendrick Gek

63 Mathias Rubichon

64 Johannes Vigelie

65 Jacob Hendrick

66 Philip Melchior Meyer

67 Johan Jerich Vansettel

68 Pieter Apfel

69 Jerich Vybert

70 Jacob Sheare

71 Michael Proops, sick

Women & Children

72 Elisabetha Margareta {Vosselman}

73 Margaret Harbyn

74 Dorothy Emich

75 Nicholas Emich

76 Johannes Emich

77 Jacob Emich

78 Marilas Shyndech

79 Cathrina Matts

80 Dorothy Rosar

81 Dorothy Kooger

82 Elisabeth Kooger

83 Barbara Hyvigh

84 Susanna Wysel

85 Ablonia Wysel

86 Barbara Wysel

87 Barbara Kuyser

88 Maris Savina [Kuyser]

89 Johan David [Kuyser]

90 Luodwick Melchionar

91 Anna Drogo

92 Maria Katrina

93 Paulina Yege

94 Katrina Moll

95 Maria Britbill

96 Anna Britbill

97 Maria Helferen

98 Christophel Helferen

99 Cathrina Spreakering

100 Maria Nagelin

101 Cathrena Shabel

102 Maria Smit

103 Maria Hausman

104 Eva Hausman

105 Magdalena Panchson

106 Andreas Panchson

107 Hendrich Panchson

108 Maria Panchson

109 Eve Panchson

110 Barbara Veymert

111 Johannes Veymert

112 Maria Gerloch

113 Anna Gluf Lowein

114 Philip Lowein

115 Christian Lowein

116 Barbara Lowein

117 Margaret Lowein

118 Anna Hugel Reyn

119 Christina Bever

120 Jacob Bever

121 Dorothy Bever

122 Barbara Lorrence

123 Maria Shooken

124 Hans Shooken

125 Maria Shooken

126 Cathrina Shooken

127 Jacob Lorrence

128 Eve Reylen

129 Jerick Reylen

130 Jacob Vry

131 Catharin Spis

132 Susanna Spis

133 Michael Proops

134 Felder Proops

135 Cathrina Miller

136 Cathrina Miller

137 Philiphbena Miller

138 Caspar Miller

139 Hans Miller

140 Michael Miller

141 Cathrina Proops

142 Anna Dubo

143 Anna Smit

144 Barbara Albrecht

145 Peter Albrecht

146 Hans Albrecht

147 Susan Husselich

148 Bernard Husselich

149 Michael Husselich

150 Maria Glassen

151 Maria Getson

152 Cathrina Trookmiller

153 Cathrina Reyl

154 Michael Reyl

155 Maria Reyl

156 Anna Martin

157 Maria Martin

158 Michael Martin

159 Magdalena Vielard

160 Charl. De Meyeren

161 Cathrina Vansettel

162 Johan Revenooch

163 Apalonia Apel

164 Sophia Rynhart

165 Anna Kootson

166 Anna Wyberton

167 Gertruy Smiden

168 Maria Vyberton

169 Susan Vyberton

Note: Numbers different from the manifest.

|

Died on the "John and William"

Johann Nicholas Boschung/Bushong and Magdalena Bushong's son,

Johann Nicholas, Jr. age four, (probable)

Hans Johannes Emich and Dorothea Emich's youngest

daughter, Magdalena, not yet one-year-old

Hans Earhart Vosselmann/Fosselmann and Elisabeth Margaretha

Vosselmann's baby daughter Eva Elizabeth

age, not yet one-year-old.

5; 6; 7

Many of the 169 new immigrants initially settled in Lancaster County and surrounding

areas in Pennsylvania, amongst family and brethren who had arrived before them. Some also moved on to territories in North Carolina, Virginia, Kentucky, and others. A few of the immigrants did not live very long after their arrival. For example, Johann Nicholas Bushong Sr. and his wife, Magdalena, likely died within a few weeks from the 1732-1733 Influenza Pandemic that was everywhere in Pennsylvania.(see article) Others from the voyage might have also caught it. Then there was Joseph Hubley, a writer critical of the Catholic church who was murdered shortly after his arrival. A man with whom he sailed from Europe killed him. The man, masquerading as a valet, was a Jesuit Priest, who came to steal Mr. Hubley's manuscripts, then kill him.8; 9; (see article) The Jesuit promptly returned to his European Catholic domain, as there would be little room for him in the heavily Protestant Pennsylvania communities.8 But of the remaining 70 some odd families? With the drive and determination they exhibited journeying to America, it was inevitable that their families would thrive. Today those families and their descendants, surely numbering in the hundreds of thousands, have become part of the history of America.

|

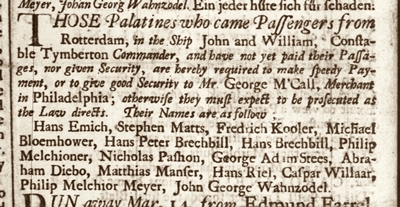

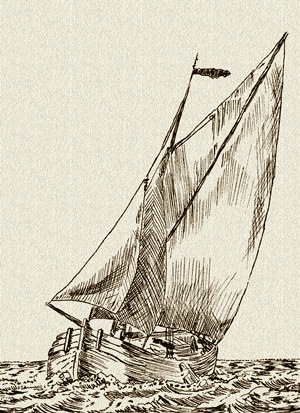

The Pennsylvania Gazette, March 8, 1733

Those Palatines who came passengers from Rotterdam in the Ship John and William, Constable

Tymberton[sic] Commander, and have not yet paid their passages, nor given security, are hereby required to

make speedy payment or to give good security to Mr. George McCall, Merchant in Phila., otherwise they must

expect to be prosecuted as the law directs. Their names are as follows: Hans Emich, Stephen Matts, Frederich Kooler, Michael Bloemhower, Hans Peter Brechbill, Hans Brechbill, Philip Melchioner, Nicholas Pashon, George Adam Stees, Abraham Diebo, Matthias Manser, Hans Riel, Casper Willser, Philip Melchioner Mayer, John George Whahnzodel.

Source: The Pennsylvania Gazette, March 8, 1733, 10. Full page of the Gazette click, here.

|

In March, the shipping company believed these fifteen men still owed for passage.

|

|

Over the next few months, down at the Philadelphia docks, Captain

Tymperton would have been overseeing, repairs and the

resupplying of the "John and William," making the boat

ready for recrossing the Atlantic. In March of 1733, the shipping company, attempting to settle its accounts, and

collect any final money owed for passage,

published this advertisement (left) in The Pennsylvania

Gazette.

These kind of advertisements were quite common in the

newspapers of the day. This one is for fifteen men from

the "John and William." Over the years, some who have

looked at this list, offered the opinion that it is a

list of the mutineers. And if as the single report

states, Abraham Diebo(Dubo), listed in the

the advertisement was one of the mutineers, then it is

possible others are on the list. But Ben

Franklin reported eight mutineers, yet the list

contains fifteen names. Besides, as the mutineers were all jailed, some from the list were not: Casper

Willser(Williar), christened a son in 1733, at the First

Reformed Church in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and was not in jail.11 Two other

passengers, Fredrick Kooler and Philip Melchioner,

arrived with the ship, but were listed as sick,

and could not have been

involved.4

In the end, it can not be

said, with any credibility, who, if any, on this list

was a mutineer or simply, had not had their fare marked

paid.

|

But it is quite likely the names of the departed

mutineers were never listed on the Ship's Passenger

Manifest, for the simple reason, that they were not on the ship when it was prepared, so of course,

they would not be listed.4 As is correct, only surviving passengers who were present were listed on manifests. That would explain seven missing passengers. Because the 169 passengers on the

Ship's Manifest, and the newspaper's reported 44 deaths

only add up to 213. The Pennsylvania Gazette reported

a total of 220 passengers boarded in Rotterdam, and that leaves seven passengers

unaccounted, who would be the mutineers. That makes a good case for the eighth mutineer being, as discussed in Part One, Abraham Dubo, who arrived with the ship. Dubo appears to have quit the mutiny and stayed aboard when the others rowed away. From that, it is possible to see that in all, Captain Tymperton lost 51 passengers on the voyage, 44 dead and eight rowed away.

Which, from the shipping company's point of view, would make over a 23% loss in passengers, as well as revenue.

|

It took over five and a half months

after her arrival, to make the "John and

William" ready, and fill her cargo holds. To put that in perspective, another ship, the ship Brtitannia arrived on September 14, 1731, and departed October 9, 1731, taking just a few weeks.

Regardless, on April 5, 1733, when the winds turned favorable, the Captain ordered the lines cast off, the ship sailed away from the

Philadelphia docks, out of the harbor, and into the Delaware River.

Next port, Lisbon, Portugal.12

As he sailed down the Delaware River, Captain

Tymperton probably had another river pilot at

the helm, possibly the same one as when they arrived. The "John and

William's" hold was inevitably full, loaded with a

combination of several commodities, wheat, flour,

beef, and pork, all prominent Pennsylvanian exports of

the day.13 How long it took for the voyage to Lisbon, was not

noted, though it was always faster sailing east. But the next report of the ship

and Captain Tymperton is, departing

Lisbon, on July 9, 1733, bound for England. It was barely 12 weeks

after their Philadelphia departure. In that time, they had already

crossed the Atlantic, discharged their cargo, taken on

any new, and resupplied the ship. So the "John and William" obviously had the potential to sail at a good clip with such a fast crossing.12

|

|

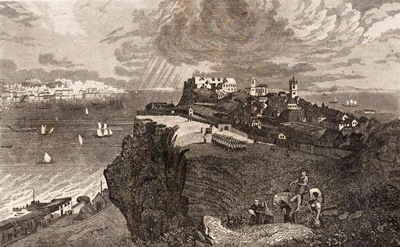

Lisbon, Portugal, the Pink "John and William's" next port of call.

|

In the summer of 1733, the "John and William" finally returned to England. Her journey had taken over 14 months. Following the cruise, Tymperton and the "John and William" parted and are not further associated. Tymperton may have resigned over the loss of the passengers and allowing a mutiny, or perhaps he was dismissed by the shipping company. Regardless, barely three and a half years later, he is found in a very different occupation.

"We hear from Scarborough, that

last Week died there the famous Dickey Dickinson,

Master of the Spaw Wells, remarkable for his Deformity

and his Impudence. The Bailiffs, we hear have

appointed Captain Tymperton, Master of Wills

Coffee House, to succeed him, a Man well known and

respected for his comical facetious Disposition. The

Corporation have resolv'd to build a new and

commodious House for the Company, on a Rock beyond

Dickey's Pier, which will be a much better Situation,

and out of Danger of any Shoots from the Cliffs, and

screen'd more from the Wind."

Source: Exposition on the Common Prayer,

February 22 1737, No.XXXII 14

|

|

|

"Behold the Governor of Scarborough Spaw,

The Uglyest Fizz and Form you ever saw;

Yet when you view the Beauty of his Mind,

In him a second Aesop you may find.

Samos unenvy'd boast Aesop

gone

And France may glory in her late Scarron

While England has a Living Dickinson."

By Dickey Dickinson

When Dickinson died in 1737, Captain

Tymperton was his successor at Scarborough Spaw.

|

|

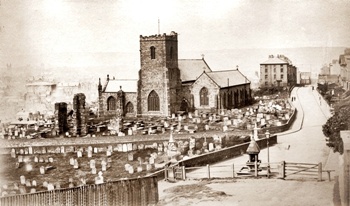

In February, 1737 Captain Tymperton was made master of the well known, Spa and Public House, "Spaw

Wells" in, Scarborough, which is a port town on the North

Seacoast of North Yorkshire, England.14 Also known as "Scarborough Spaw," it had a Public House, or commonly called a "Pub" that likely served as a coffeehouse. Captain Tymperton's experience at Will's Coffeehouse is a good indicator of that as well as it's former master, Dickinson, who was illustrated with a coffeepot, sitting next to him. The spa was a unique Scarborough area attraction for many years. Discovered in about 1660, it had natural spring water bubbling out beneath the cliff to the south of the town. The water stained the local rocks a dark brown color with a reddish-orange tinge - also described as a russet color. Its flavor was slightly bitter and thought to be a cure for minor ailments.

Richard "Dickey" Dickinson secured the lease on the spa's land in the early 1700s. By 1725 he had become notorious enough to be the subject of several etchings.36 The spa, when Dickinson got it, was no more than a barrel to collect the water. He had constructed his house and several buildings, all along, promoting its health benefits.37 The fame of the water's medicinal effects soon spread and, drinking the spa waters became an accepted medicine as well as fashionable. Dickinson had an abundance of customers.15 It seems possible that since the waters were mixed, with wine at dinners, that they were also used in the coffee, making a singularly unique caffeinated concoction as well as a remarkable experience.38

As mentioned, before 1737, Captain Tymperton had been the master of Will's Coffeehouse, in London.14

Located on Russell Street in Covent Garden, beginning in the 1660s, Will's, was a very well

known and popular coffeehouse. But by the time Captain Tymperton was master, it had been past its prime for several years.16 It is an easy assumption

that Captain Tymperton had been at Will's since shortly after the cruise ended. It would take a year or two and possibly the entire three and a half years, to have gained the

experience as well as the notoriety to become the replacement for

the legendary Dickey Dickinson. Passing away on Sunday, February 12, 1737, Dickinson, the self-proclaimed "Governor of Scarborough Spaw," was described in newspapers as

"remarkable for his Deformity and his Impudence." 12. Running the spa, Dickinson had become a celebrity, well known for his poetry and cutting wit. He had honed his skills, defending himself from insults about his abundant physical deformities. So, finding a successor for him would indeed be a challenge.

|

To understand coffee and coffeehouses in the day, England, beginning in 1650

with the opening of its first coffeehouse, coffee

became the rage.17 In general, the drinking water in the day was not very clean, and for hundreds of years, many

had chosen alcohol, usually beer, ale, or wine, which was safer to drink. So, when people began

drinking coffee instead of alcohol, the new experience

of being alert from the caffeine instead of drunk or

semi-drunk was novel and uplifting. So uplifting, the houses were commonly called "Penny Universities", in reference to their intellectual banter as well as the price per cup - a penny.18 Their caffeinated and talkative clientele were highly enthusiastic about their coffee and their newly discovered wits.

So it would be all the more important to have a good Master of the Coffeehouse. He was responsible for setting and maintaining the tenor and tone of their banter. It is interesting that when describing their choice for the New Master of Spaw Wells, the Spa's Corporation described Captain Tymperton as

"a Man well known and respected for his comical facetious Disposition." 12 They felt these were necessary qualities that were needed to replace Dickinson in what would end up, a completely new establishment. That, following a freak earthquake on December 29, 1736, that knocked Dickinson's house down the hill and completely covered the old spa. In all, about an acre of land collapsed. Ironically, Dickey Dickinson would soon be gone too. Without a house and deprived of his spa's healing waters, and possibly his coffee, he fell ill and was dead within six weeks.19 For more about Dickey Dickinson, on this website, click here.

|

|

"Think not to find one meant

resemblance there, we lash the

Vices but the Persons spare." Said to be St.

John's Coffeehouse, Shire Lane, London in 1732 or

1733. By William Hogarth. Note: the clock says four, probably in the morning, and the time for coffee was long past, with these gentlemen.

|

|

William Tymperton was buried at the St. Mary's Church in Scarborough in 1755.

|

|

Transcribed from the London Magazine:

"It is stated that Dickinson was buried at the old

church at Scarborough, but there does not appear that

any monument was erected to him. On a flat stone,

facing the south entrance of that church, is inserted

a metal plate bearing the following inscription to the

memory of Dicky Dickinson's successor in office:"

"Here lyeth the body of Mr. William Tymperton, late

Governour of Scarborough Spaw, who departed this Life

on the 12th day of January, 1755, aged 65."

Source: Notes and Queries

Published 1860, Page 109 21

|

|

|

Captain Tymperton proved to be a good

host and master of the well-known spa and coffeehouse and

remained the Governor of Scarborough Spaw for the rest of his

life. Though he had first married Elizabeth Esh, March 10, 1721, he later married, June 9, 1746, at St. Katherine by the

Tower, in London to Elizabeth Briggs. Again, on April 19,

1750, he married Elizabeth Harrison, also at St.

Katherine's.20; 39 It is

interesting, in all three marriages, he used his prior title, Constable Tymperton.20; 39 Just

over 22 years, after the "John and William's"

crossing, Constable William Tymperton died, January

12, 1755. He was buried in the Scarborough Church

Cemetery, in North Yorkshire, England.21

|

We have an Account,

that the John and William, ——, bound from Cape Fare to

Bristol, was lately taken by a French Privateer; but was lost

before she reached her Port.

Glasgow Courant, March 7-14, 1748

22

|

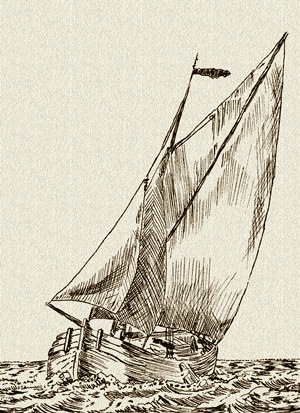

As for the Pink "John and William," of Sunderland,

after Captain Tymperton's command, she apparently had many good years of service left in her.

How long could she have survived?

A ship's life span

in the day, varied from either 10 to 12 years, or 20

to 25 years, depending on whether it was a poorly built

or a well-built vessel.23 If

she was of Dutch origin, as her design indicates, then

with their reputation for well-built boats, she could

have lasted up to 25 years, if her usage was not too

hard. So depending on her age in 1732, the "John and

William" could have lasted maybe into the 1750s. Some

ships were in service for so many years that after they were filled, with cargo, such as lumber, chains were wrapped around the hulls and were screwed tight, to keep them from coming

apart.23

But there is nothing heard of a "John and William" until 1748. Though there was a later "John and William," noted, for example: in 1792, and it was a much larger Brig, there are no others found before.24

So, perhaps the sinking in 1748, of a ship

named "John and William," near Cape Fear (also called

Cape Fare), North Carolina, was the end of the

Pink "John and William." And it seems possible,

because with the area's shallow water and numerous

treacherous shoals, a ship with a shallow draft like a

"pink" would be ideal. The cape became named

"Cape Fear" in 1585, because its shallows and

shoals were so dangerous that the first expedition

sent there, ran aground. Partially because of that, it

is considered part of the so-called Graveyard of the

Atlantic.25

|

|

|

|

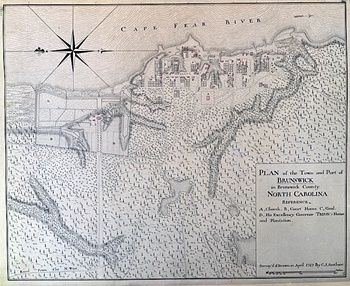

A Brunswick Map from

1769. Brunswick, along with Wilmington, were the two ports of entry for North Carolina.

|

|

The blockade of the North American Coast by the French and Spanish Privateers started soon after the beginning of the second French and Indian

War - "King George's War". From 1746, as it dragged on, the North

Carolina coast became more and more dominated by

privateer ships, until they virtually strangled shipping. North Carolina's and much of the Atlantic Coast was high risk in the shipping business as each voyage became a dangerous venture. There were many British

ships reported captured or sunk. as the Privateers lay

off Cape Fear, attacking anything flying a British

flag. By 1748, the area was virtually in their control.26

The Privateers even captured ports taking or sinking any ships they wanted. It happened within a month or two of the "John and William" sinking, on April 6, 1748, when the Spanish boldly sailed into the Cape Fear River. They captured

and plundered Brunswick, one of the two ports in the

bay. The British later mounted a counter-attack and recaptured it, but the Privateers were pretty much in control and were causing significant damage and chaos.27 To attempt to run a

ship through them had to be desperate, but to run a slower ship,

like the "John and William" would be foolhardy, indeed.

A ship would have to haul valuable cargo to justify

such risks.

|

From North Carolina to Bristol, we can only surmise what cargo the "John and William" was carrying, in 1748, because any shipping manifest she might have had has yet to be discovered, or went down with the ship. In the period, the most common exports from North Carolina were lumber, and its other products tar, pitch, and spirit of turpentine. These were all manufactured from the pine trees that forested much of the region. They were all essential supplies used for the construction and repair of sailing ships and were known as "Naval stores". North Carolina was an important supplier of Naval stores to Britain, who needed more boats with which to fight the war. Keeping this in mind, Naval stores were most likely her cargo.28

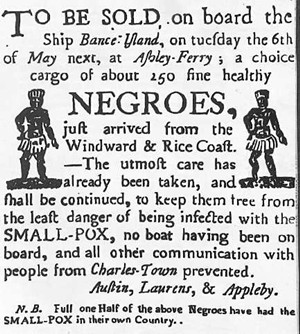

But Naval stores would surely not be considered a valuable cargo for such risks, at least from a monetary point of view. So it was likely that their prior cargo, to North Carolina, had made the stakes worthwhile. In this light, and considering the "John and William's" "North Carolina - Bristol Route," it now raises the specter of the slave

trade. Specifically, the Bristol Slave

Trade, in which both Bristol and North Carolina

were deeply involved. A cargo of slaves would also fit nicely into the ongoing business model of Triangular Trade. That

typically describes commercial voyages between three

ports, in this case, Bristol, to Africa, then to the Americas, and

back to Bristol. Trade goods from England, taken to Africa, were either sold or traded for newly captured African slaves. Then the slaves were taken to the Americas and were sold. The

ships then returned to Bristol with money and commodities from the

Americas.29

Between 1697 and 1807, Bristol ships carried 2,108 shiploads of slaves from Africa to the Americas. They averaged

twenty slaving voyages a year. The result was,

approximately 500,000 Africans were captured and brought

into enslavement by Bristol ships, representing

one-fifth of the entire British slave trade

during this time.30 In the early 1700s, profits

from the slave trade were very lucrative and ranged

from 50% to even 100%. The City of Bristol, already

comparatively wealthy, became an integral part of the slave triangle, the riches rolled in, Ultimately the city with its many shipping companies, dealing in slaves, grew very

rich.29; 31

|

|

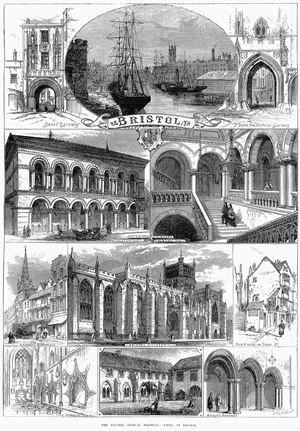

The Grandeur of Bristol in 1879. Said to be built on the profits of the slave trade.

|

|

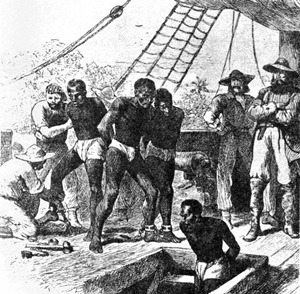

Captured Africans, are loaded into the hold of a

ship. The "John and William" could probably hold

more slaves than the 220 passengers in 1732.

|

|

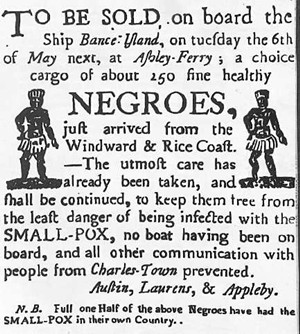

So, was the "John and William" used as a slave ship in 1747 and 1748? Well, sixteen years earlier, in 1732, the ship's owners and shipping company were already utilizing Triangular Trade and had proven they were willing to deal in human cargo, with the 220 immigrants. Then, the ship was well suited for the waters around the Cape Fear Shoals and capable of carrying at least 220 slaves. That would be a nice load - the advertisement below, from a larger ship, lists 250 slaves for sale. And finally, there is the unavoidable fact that by now, the "John and William" was an older ship, with at least sixteen years on her, and likely several more. She was approaching the end of her useful life. The shipping company undoubtedly knew the risks. England was well aware of the blockade, from lists of losses published in newspapers that were full of notices of ships sunk. But they would use an older "John and William" in risky crossings and not be too concerned if she were lost to the blockade, especially considering every load of slaves was hugely profitable. That said, it seems well within the realm of possibility that she was a slave ship.

Further, the Ports of Brunswick and Wilmington, on the

Cape Fear River, in North Carolina, were prime ports

for slave ships due to their accessibility.32 By the 1800s, enslaved Africans in the port areas and Wilmington outnumbered whites 2 to 1.

Not only was their labor heavily relied on, but also their

skills in carpentry, masonry, and construction, as

well as sailing and boating.33 Thousands of enslaved Africans were brought to the Carolinas, in the 1740s, alone, and the "John and William" could easily have been one of the ships

caught up in their enslavement.34

|

Trying to narrow down when the "John and William" sank, the March 7-14 newspaper reported it happened

"lately". It would be safe to assume it took at

least a month or so for the word of the event to reach

Glasgow, as such, it probably was before the middle of

February. But with so much delay in the news of the

day, it could have been before. Regardless, when

the "John and William" sailed from Cape Fear, North

Carolina en route to Bristol, England, she was captured

by the French Privateers. From there, she never made

it to port, and that was the last heard of

her. It is possible either the "John and William" sank

from damage caused in her capture, possibly while

making a desperate run to a port. Or more likely, the

Privateers easily captured the smaller, slower, and barely armed "John and William" and having no use for the cargo or the

ship scuttled her, or in other words, purposely sank her, to prevent her and her cargo from falling back into English hands.

Either way, she sank, settling on the

bottom of the ocean, probably not too far from Cape Fear. One more ship in the Atlantic Graveyard.

We can perhaps imagine, as the seas poured in, beginning to sink the now older "John and William," her timbers must have creaked and groaned in protest. She was probably pulled under quickly. In contrast, sixteen years earlier, as the bodies of her dead immigrants fell into the sea, they sank slowly and silently.

The End

|

|

A newspaper advertisement from 1760, for the sale

of slaves, at Ashley Ferry outside of Charleston, South Carolina. Published: The Charleston Gazette, April 26, 1760 35

|

This

Article is Copyright ©2020 by Rick Bushong and

Commercial Use is Prohibited.

Non-commercial use is

permitted if copyright information is

included.

|

References for Epilogue:

- "Journey to Pennsylvania in the Year 1750 and Return to Germany in the Year 1754" By: Gottlieb Mittelberger, Published 1756

- The John Naas Letter, of the Crossing on the "Pennsylvania Merchant" 1733

- The

Keck House

- Transcriber's Guild, Pink "John and William" Passenger List

- Direct

Search the Bushong United Family Tree

database.

- Magdalena Emich

- Vosselmann baby, Eva Elizabeth

- Notes and Queries: Historical, Biographical and Genealogical,

edited by William Henry Egle, Published 1898 Page 200

- Murder Lurks on the Pink "John and William"

- The Pennsylvania Gazette, March 8, 1733, Page 2

- FamilySearch.org Casper Williser

- The Pennsylvania Gazette, April 5, 1733, John & William, Constable Tymperton, to Lisbon.

Page 2

- Colonial America in the Eighteenth Century, by James T. Lemon,

Page 13

- Exposition on the Common Prayer, February 22 1737, No.XXXII

- Wikipedia: The Spa, Scarborough

- Wikipedia: Will's Coffee House

- Wikipedia: Coffeehouses

- Turkish Coffee World History of Coffee

- Exposition on the Common Prayer, January 11, 1737, Number XXVI

- Guildhall Library Manuscripts: index to

St Katharine by the Tower marriage licence records

Tower

marriage licence records

- Notes and Queries for Readers and Writers, Collectors, Volume 9 Page 109

- Glasgow Courant, March 7-14, 1748

- Aspects of Capital Investment in Great

Britain 1750-1850: A Preliminary Survey, By S.

Pollard, J.P.P Higgins, Published 1971, page 155 and 156

- The Universal British Directory of Trade, Commerce,, Volume 4

By Peter Barfoot, John Wilkes, Page

748

- Wikipedia: Cape Fear (area)

- The Royal Colony of North Carolina, King George's War of 1744-1748

- A Maritime History and Survey of the Cape Fear and Northeast Cape Fear Rivers, Wilmington Harbor, North Carolina, By Claude V. Jackson, 1996, Volume 1

- Learn

North Carolina

- BBC - Legacies - Immigration and Emigration - England - Bristol - Legacies of the Slave Trade Page 2

- BBC - Legacies - Immigration and Emigration - England - Bristol - Legacies of the Slave Trade Page 1

- Port Cities of Bristol

- North Carolina Office of Archives and History

The Town of Brunswick

- Slavery in North Carolina

- The Abolition of the Slave Trade slave imports

- Published: The Charleston Gazette, April 26, 1760

- Notes and Queries, July - December 1856

Page 273

- The Ephemera Society Scarborough Spaw

- A Journey from London to Scarborough, in Several Letters from a Gentleman: page 40

- FamilySearch.org

- Historic Homes and Institutions, page 34

Further Reading On Bushong United:

Further Reading:

- Anecdotae Eboracenses: Yorkshire anecdotes; or remarkable incidents in the ...

By Richard Vickerman Taylor. Published 1887 Page 81

- Greater Than the Mountains Was He: The True Story of Johann Jacob Shook of Haywood County, North Carolina.

By Wilma Hicks Simpson Published 2013 click here

- Pennsylvania Germans, A Persistent Minority. William T. Parsons. Collegeville, PA: Chestnut Books, 1985,

- The German immigration into Pennsylvania through the

port of Philadelphia from 1700 to 1775 part II: The

Redemptioners, by Frank Ried Diffenderffer, Published

1900

click here

- The English Spa, 1560-1815: A Social History, By Phyllis May Hembry, Published 1990 click here

|

|