| The Immigrant - Johann Nicholas Boschung |

|

|

The Immigrant

Johann Nicholăs Boschŭng

Germany to Pennsylvania

By Rick Bushong

January 9, 2015

Expanded and integrated with Andrew's article: May, 2018

Revised: October 24, 2021

|

The Claudian Tree, by Erik Koeppel

|

Johann Nicholăs Boschŭng

| |

* * |

Johann Nicholăs Boschŭng

About 1693-October 1732

|

|

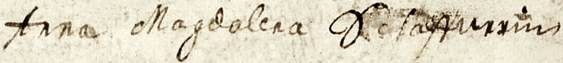

Anna Magdalena Schaffner

January 27 1698-October 1732 |

*From church books - 1715, in the clerics hand.

Married October 15, 1715

Their Children

- Maria Barbara Boschung

- Anthony Andrew Bushong

- Maria Barbara Juliana Bushong (Meixel)

- George Henry Bushong

- Eva Elisabetha Bushong (Schwartz)

- Johann Nicholas Boschung Jr

- Anna Maria Boschung

|

For the sake of clarity Hans John Bushong the 1731 immigrant is labeled (IV) and his father, the 1719 immigrant is labeled (III).

|

Like his father and brother, Nicholas could have been looking for a new start, where land was cheap and where his religious beliefs could not be outlawed. Or he could have been rushing to America to see an ailing father. It is not known. Either way, he and his family risked it all and left their German village to sail to America. On the voyage, they endured intense hardship, hunger, and even the loss of a son and infant daughter. Then within a short time of landing in Philadelphia, both Nicholas and Magdalena were tragically and unexplainably dead, leaving four children. With such a rapid demise, there is little to prove they ever existed in America.

So far, there are no will, estate, or guardianship papers and no tombstones. Only their names on a manifest, a couple of proud signatures on the Oaths of Allegiance and Abjuration, and then an advertisement, for unpaid passage, in the Pennsylvania Gazette. But nothing else. With so little to go on it almost seems as if they never existed. But to think that when Nicholas and Magdalena died, their hopes and dreams for new lives died too, would be wrong. Those dreams would come to pass. Only they would be realized by their children and children's children, who grew up, and many had successful lives. Their descendants not only prospered, but they also multiplied. And now a fair portion of all the Bushongs in America can call them not just ancestors, but family.

|

Johann Nicholăs Boschŭng of Germany |

The enigmatic Johann Nicholas Boschung, who went by Nicholas, was born sometime around 1693, in what is now Minfeld, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. With church records still being searched, his date of birth is just a guess, and the place is an assumption. However, beginning in 1682, at least two siblings were born there.1 He was a son of a German-Swiss, Hans John Boschung III who was born in Oberwil, Simmental, Bern, Switzerland, and Anna Maria Boschung.1; 2

In 1699, as a boy, Nicholas moved with his family from Minfeld, some 41 miles, (66 km), to Stelzenberg, Kaiserslautern, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.3 Then sometime before 1715, Nicholas had moved a little less than seven miles (10 km), to Schmalenberg, Súdwestpfalz, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Schmalenberg never was a large town and even as of 2017 there were only an estimated 759 residents.4 But eventually Nicholas lived there over seventeen years and met his future wife. On a Tuesday, October 15, 1715, Nicholas and Anna Magdalena Schaffner were married in their village.5; 6; View original Magdalena, who was born there and baptized January 27, 1698,5; View original was a daughter of Samuel Schaffner and Anna Margaretha Klein. Samuel was born in 1664 in Granichen, Aargau, Switzerland and he died in 1717 in Schmalenberg. His wife Margaretha was born 1676 in Schmalenberg and also died there, in 1736.1

Nicholas and Magdalena lived in the tiny village and a month following their marriage, November 15, 1715, their first daughter, Maria Barbara was born.1; 5; 6; View Original. Sadly she died, apparently as an infant. Their next five children were also born in Schmalenberg. They were baptized in the Reformed Parishes, some in Schopp,5; 6; 7: which was about five miles (7.7 km), others in Waldfischbach,5; 6; 7: less than seven miles away. Their last child, a daughter, Anna Maria was born in Rotterdam, a few days before they sailed to America.28

From church records their birth dates and baptismal names are given:

- Maria Barbara November 15, 1715 (died young)

- Johann Andreas January 30, 1717

- Maria Barbara February 4, 1719

- Johann Henrich January 30, 1722

- Eva Elisabetha March 9, 1724

- Johann Nicolas (Jr.) April 26, 1727

- Anna Maria (baptized) June 17, 1732

|

|

|

At least two of Nicholas' siblings and likely Nicholas, were baptized in the church located on the outskirts of Minfeld. The Minfeld Protestant Church was built on the edge of a slope in the second half of the 11th century. Inside fresco paintings adorn the walls from the various stages of its construction. Currently they are restoring frescos from the 13th and 16th centuries.

Photo by Rudolf Wild, compliments of Wikipedia.

At least two of Nicholas' siblings and likely Nicholas, were baptized in the church located on the outskirts of Minfeld. The Minfeld Protestant Church was built on the edge of a slope in the second half of the 11th century. Inside fresco paintings adorn the walls from the various stages of its construction. Currently they are restoring frescos from the 13th and 16th centuries.

Photo by Rudolf Wild, compliments of Wikipedia. |

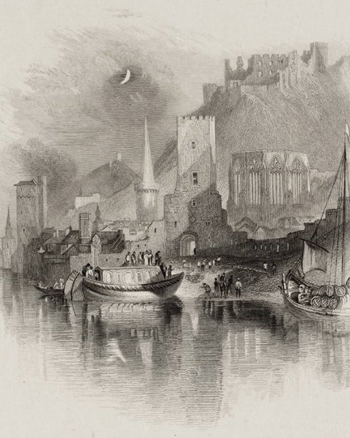

On March 25, 1731, Nicholas and his family were last documented in Germany, when their oldest child Andreas was confirmed in the church. It was at Easter service in the Waldfischbach Reformed Parish, and he was fourteen years old.6 Having made the fateful decision to go to America, in the spring of 1732, the family packed up and made arrangements to leave. They were not the first Boschungs to go and were following in the footsteps of his father and brother. In the middle of April, likely a little late, they began their fateful journey. Nicholas and Magdalena, who was now seven months pregnant,28 and their five children (ages five to fifteen) left their village. Traveling further, they were to depart their country and Europe altogether, to immigrate to Pennsylvania.

|

|

Nicholas' journey out of the Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

meant traveling on the Rhine River to Rotterdam. A few miles,

(16.6 km),

down the river, they would have passed the town of Bacharach, shown in this illustration.

Titled: Bacharach on the Rhine.

Drawn by J. W. M. Turner,

(etching by E. Fiden), Published 1832.

|

|

1732 - The Journey to Pennsylvania

The prior year, about 600 immigrants came to America from Rotterdam. However, 1732 became an exodus, and the refugees and their encampment swelled. Ultimately 2,095 ended up immigrating to the colonies, most of whom were German.8; 9 And those are just the paying customers. When those who could not find a ship or the infants, children under five, and others never listed are considered, the throng was in the thousands. Period reports indicate that it could take a few weeks to locate a ship. But with such crowds, it could very well have taken longer. When the Boschungs finally arrived in Rotterdam, they probably were surprised to see so many others waiting for boats and may have wished they had left sooner. Nevertheless, sometime in June, Nicholas booked passage on the ill-fated voyage of the Pink "John and William" with Ship's Master, William Tymperton.8

"Pink" is from the Dutch word "pincke" and it translates to "pinched". A pink was described as any small ship with a narrow stern that usually had a flat bottom. They had a large cargo capacity, but were not usually used for transatlantic transportation.8

Period records confirm that the "John and William" was one of the smallest ships used in the Colonial immigrations and also that this voyage was Tymperton's and the Pink "John & William's" only transatlantic crossing, at least with immigrants.8 But the Boschung family now had a way to America. After buying any last supplies and fresh food, they were ready. But before boarding the tiny ship, there was one more thing to do. Magdalena had since given birth, and it was likely within the week and probably in the refugee camp. Then on a clear day, it was June 17th, and with the wind blowing eastwardly,29 the boat and its master were probably eager to set sail. Still, Nicholas and Magdalena took their new daughter to Rotterdam's Dutch Reformed Church and baptized her Anna Maria.

|

Within a day or so, the ship had its final passengers and cargo aboard and was ready. With the favorable winds and tide, they sailed away from Europe.29 Next, the Captain sailed to England and dropped anchor in Dover. The stop in England was required for the voyagers to gain permission to immigrate to the British Colony. When all were approved, the "John & William" sailed out of Dover and began its infamous Atlantic crossing, which with their transit time to Dover would end up totaling seventeen weeks.10 The usual time for the voyage was eight or nine weeks, and during this voyage, which was almost twice as long, forty-four passengers died. Sadly among the dead were undoubtedly Nicholas' son, five-year-old Johann Nicholas Jr., and his sister, Anna Marie, who was but a few weeks old. On these early voyages, the odds for children under five surviving were so poor that the shipping companies could not charge their parents. They were not even listed on passenger manifests if they lived through the trip.11 Then, in the 14th week of the voyage, long past their scheduled arrival, with everyone slowly starving, some of the passengers took control of the ship. The blame can only go to Captain Tymperton, who chose to stop in Dover, making the voyage longer. Then he proved so inept that he allowed eight starving passengers to succeed in a mutiny.10

Ultimately the mutineers only prolonged everyone's suffering as well as the voyage. This because, after sighting the American coast and the entrance of the Delaware Bay, the mutineers, who needed a place to escape, ordered the ship to sail south. They sailed as far as the Virginian Territories and back, twice. Eventually, they stole a ship's dingy and rowed to the New Jersey side of the entrance to the Delaware Bay. Then the ship continued to Philadelphia. It would take at least another week sailing up the Delaware River before the voyagers and "John and William" happily entered the Philadelphia harbor. It was Sunday, October, yet they were still required to remain on board until all passengers were cleared for contagious diseases and settled their dept with the shipping company.11; Read the full story.

|

|

Their journey began in Schmalenberg in the spring of 1732. Map provided by Google Maps, © by Google all rights reserved.

|

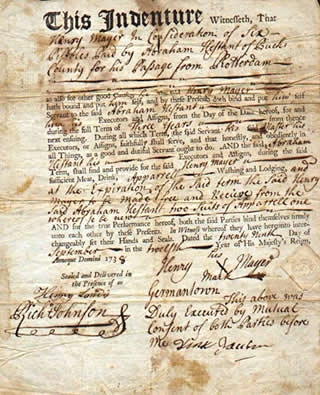

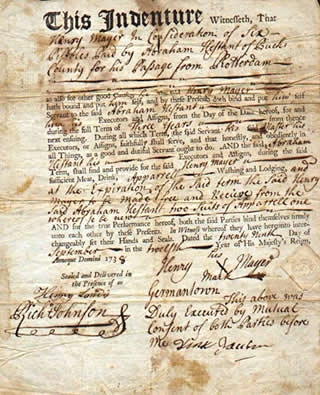

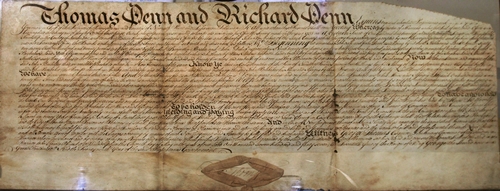

An actual indenture certificate,

this one from 1738, Germantown.

|

|

Arriving in Philadelphia - Indentured or Passage Paid?

Mittelberger also elaborated, "Adult persons bind themselves in writing to serve 3, 4, 5, or 6 years for the amount due by them, according to their age and strength. But very young people, from 10 to 15 years, must serve till they are 21 years old." In the case of Nicholas and Hans, it is safe to assume that neither they nor anyone in their family were indentured. It appears they could pay for their passage, from a couple of points.

|

The first is Nicholas' brother Hans John IV, and son, Andrew's 1734 Lancaster County property ownership. This is determined from a Land Warrant (discussed below).13 Andrew being underage could only receive it through a gift or inheritance.14 Regardless, in less than two years he owned property, which precludes indenture in its own right.11; 16 The same is true for Hans, as it would not be possible to spend two years (as a minimum) indentured, getting paid nothing, and then in the beginning of 1734, to have saved the money to buy property.

The other indication Nicholas was not indentured was an advertisement in The Pennsylvania Gazette, March 15, 1733. It lists Nicholas Pashon, and others from the ship still needing to pay for passage.15 This appears to be a spelling mistake in the Ship's Manifest, which was made immediately upon arrival. This determined how many passengers survived so they could be charged for the voyage. As passengers settled their fares their names were compared with the Ships Manifest.

But when Nicholas reported to the scribe who was making the manifest he did not correct a misspelling and the scribe wrote something like "Panshon" for "Boschung," and also for Magdalena and the children. When Nicholas actually paid they could not find his name. In the rush to leave the ship and get to shore, the scribe-treasurer and Johann Nicholas Boschung settled his family's fare and his name was noted, only as Boschung. The shipping company had not reconciled that the two listings were the same family. So regardless, Nicholas was off the ship. Besides, if he had been indentured it would have involved a third party, or more precisely, the new owner who had to pay the fares. So it would have been noted in the extra paperwork.

|

|

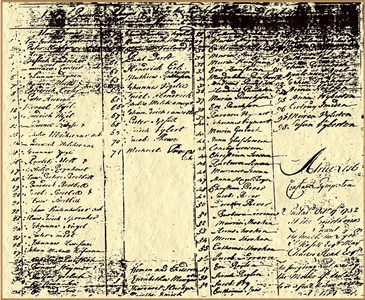

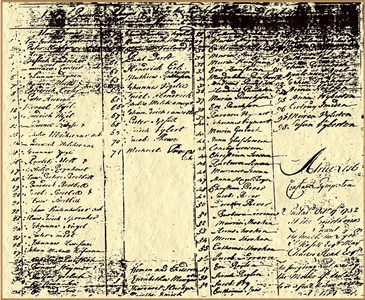

The Pink "John and William" passenger manifest. Spelled as Panshon, Nicholas is number 28, and Magdalena and children start at 34 (of the woman and children). 34. Magdalena Panchson, 35. Andreas Panchson, 36. Hendrich Panchson, 37. Maria Panchson, 38. Eve Panchson. Copy from Pennsylvania Archives.

|

|

|

|

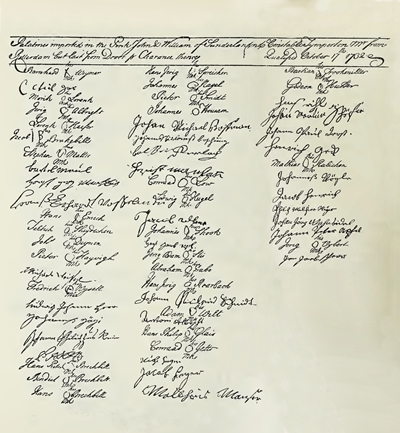

The Pink John and William's" Oath of Allegiance, October 17, 1732. Nicholas' signature is located in the center, sixth from the top and below fellow passenger, Johann Michel Hoffman's similar signature.

|

|

Nicholas Bushong in Pennsylvania

|

It is a foregone conclusion that Hans John Bushong IV, who immigrated in 1731, and Nicholas Bushong are related and inevitably brothers. Given the rarity of the Bushong/Boschung surname, both brothers arriving a year apart, the previously mentioned associations with property, and the fact that Andrew witnessed Hans' 1749 will. On their own, these facts are sufficient to make the genealogical connection. But perhaps more convincing is the evidence from the DNA tests on descendants of Hans and Nicholas which proved they had a very close relationship.15; Read article

When Nicholas finally reached the safety and comfort of his family's home, he, Magdalena and the surviving children numbered six.8 But a valid question would be, what kind of house had Hans been able to build in the year since he immigrated? Hans and his wife Barbara had five children, including a newborn son, John (V), not even two months old.18 Could Hans have built a home or cabin that could house and keep all thirteen of them warm and secure? It seems unlikely. A more realistic scenario would be that they were able to stay at their father's home. Their father, Hans John Bushong III, had lived in Pennsylvania for years.8 He would have had ample time to make a solid, if not a nice large home, which was probably the case.

However, with his brother Hans and young Andrew both owning adjoining property, it appears their father and grandfather, Hans John III had died before then. The simplest explanation is Hans and Nicholas had inherited their father's property, and when Nicholas died his passed to Andrew. Unfortunately, there are no Civic records or any documents found to prove it. And it is also true of Civic records for Nicholas and Magdalena. Absent these, no other conclusion is possible except that they had also died and shortly after their arrival.

|

Later on, May 19, 1739, supporting this, Nicholas, as would be expected, is missing from a list naturalizing virtually every German (or Swiss-German) in Lancaster County. Hans John Bushong IV is the only Bushong on it.19. So Nicholas, as well as his father, died before then. Besides, Andrew's underage land ownership is a huge clue.13 It was before the land survey on October 16, 1734, and probably closer to February 28, 1734, when his uncle's land warrant was dated. Andrew was just seventeen years old and already owned property. Also, his property was adjoining Hans Burhan's 200 acres. In other words, they lived next door to each other.13 By law, Andrew could not enter into a binding contract for anything including land, until he was twenty-one years old.14 It leads to the inescapable conclusion that Andrew's land was inherited.14

|

|

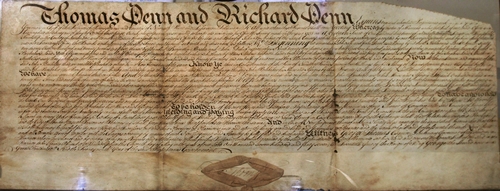

An original 1747 Land Grant to Hans Brubaker(A-1), 1695-1748, for 125 acres in the Hemphill Township. His son John was good friends with Martin and Juliana Bushong Meixel, as seen in Martin's 1788 will. Martin was Nicholas' son-in-law.

|

It also proves Nicholas and Magdalena were dead and the valuable land warrant or land grant had successfully passed to Andrew, the oldest son. We cannot say how they died. Maybe they never recovered from the hardships of their voyage? There was also a border dispute with Maryland with violent raids into Lancaster County continued between 1730 and 1738.20

November 23, 173223

November 23, 173223 | |

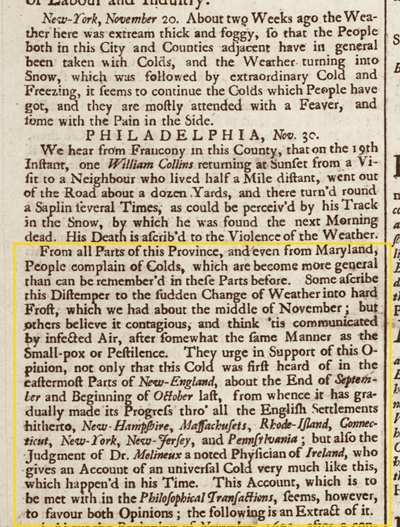

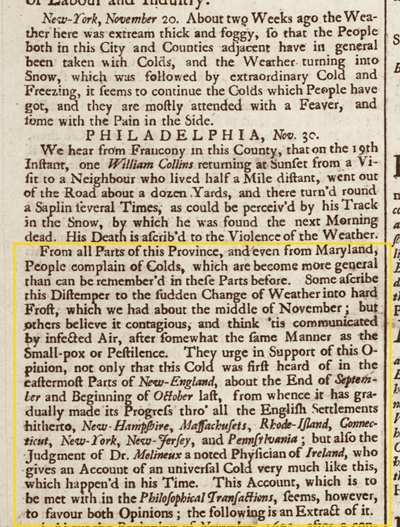

Yet, perhaps a brief but foreboding report from Boston sent, October 2, could cast some light on what happened. Published in Ben Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette, it was for the October 9 to 19th, 1732, period.

"This Town was scarce ever so universally afflicted with Colds as this Time, which made our Assemblies yesterday appear very thin, there being scarce Voices enough left to carry on the publick Singing. We hear that the same prevails throughout the Country, especially in the Towns to the Eastward."10; view source

That is the same issue that reported the "John and William's" mutiny and arrival. The report appears to herald the beginning of the sickness and its entry into the colonies. Further, it was two weeks old, and in Boston, everyone was so sick, few could attend church services. The illness quickly engulfed the colonies, and it was clearly in Philadelphia by the middle of October. By October 25, two of New Port, Rhode Island's large churches closed because their ministers and most of their congregations were ill with colds and fevers.21; view source;

full page

By November 23rd, Philadelphia reported many people with "violent Colds." 22; view source; full page By

November 30th, some people were beginning to understand.

.... others believe it contagious, and think 'tis communicated by infected Air, after somewhat the same Manner as the Small-pox or Pestilence. They urge in Support of this Opinion, not only that this Cold was first heard of in the eastermst Parts of New England, about the End of September and the Beginning of October last, from whence it has gradually made Progress thro' all the English Settlements hitherto, New Hampshire, Massachusets, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania; .... [sic]23

It would be another 120 years before they would be discovered and named "Germs" by Louis Pasteur. Yet in 1732, some realized whatever it was, it was transmitted through the air and it was infected air.

|

Eventually almost everyone caught it, and on December 7, 1732, Mr. Franklin described its effects: "many elderly people die among us of Colds, and the Pleurisy has taken several Young People lately." 24; view source; full page 1; full page 2.

Fall and winter of 1732 and 1733, found many people sick and some dying from Franklin's "violent Colds." Many years later, the sickness was diagnosed and it was more dangerous than a cold. It was a flu that became a worldwide epidemic.25; 26

|

Winter arrived early in November, with frost and freezing weather, making life more difficult. But more seriously, Pennsylvania and the Colonies were in the grip of an influenza epidemic, the likes of which had not been seen in over 100 years. This flu was not only highly infectious, it was a particularly strong influenza strain that became known as the 1732-1733 Influenza Pandemic.25 It further seems that in July 1733 it even found its way down to the new colony of Savannah, Georgia. Here it was responsible for an extraordinarily lethal 13% mortality rate!26 This with Ben Franklin's reporting makes it clear the virus had spread throughout most of the new world.10; 21; 22; 23; 24 The flu strain of the 1732-1733 pandemic was eventually identified as the "Russian flu" which first appeared in 1729, but did not reach epidemic at worldwide levels until 1732.25

|

|

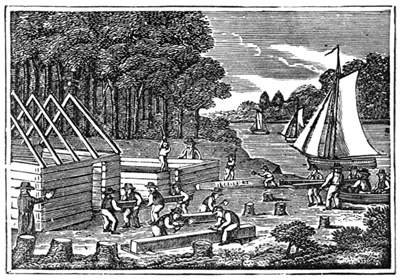

Building a cabin in Colonial Pennsylvania. |

Regardless, in their conditions, Nicholas and Magdalena, both weakened and severely undernourished from the long voyage, this epidemic would have easily proved fatal. So, their deaths may have been inevitable. But perhaps once in America, they simply let their guard down a little too early. In the commotion and confusion of Philadelphia, they would have been meeting so many people. Then on the road to Lancaster for a week or so, all while not recovered. When it is considered, from the moment they left the ship, there were abundant opportunities for their unwitting exposure to the virus. Sadly, they would have perished within just a week or two, which unfortunately seems a likely explanation. It is ironic that after so many months and such a journey, they would live in America so briefly, only to be brought down by something as small as a flu germ. If this is the case, it was probably towards the end of October 1732, when Nicholas and Magdalena passed away. As often true, it was likely from the secondary complications associated with flu, but their debilitated conditions certainly would have contributed.

Yet whenever it happened, they were in a house his father had built and maybe in his father's bed. And perhaps we can take comfort that when they died, Nicholas and Magdalena had in effect, "made it home." They would be warm and made comfortable, as much as possible, but more importantly, they were in the arms of their family, their loved ones, and their four children who survived. When they died, Nicholas was probably just under forty years old. Magdalena likely hadn't reached her thirty-fourth birthday. It was surely a sick and miserable Bushong family, and likely everyone was infected. It might have fallen on Andrew and Hans to bury Nicholas' and Magdalena's remains. For the rest of their lives, they, of course, would have remembered digging the graves in that freezing winter, and where they were. Sadly for us, we will likely never know. But wherever it is... "May they rest in peace."

|

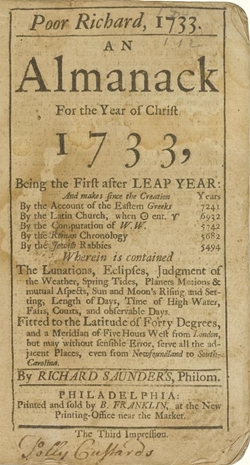

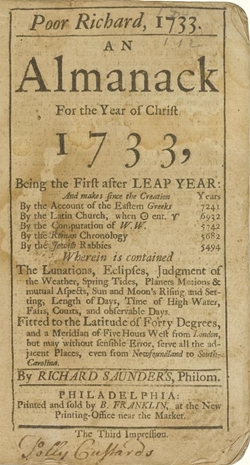

The Bushong families very well could have read and sought advice in Poor Richard's Almanac, which was first published in 1732. It was so successful, that Ben Franklin ran three printings of the first edition as late as January 1733.

|

|

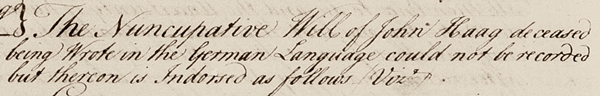

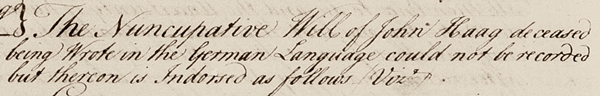

There has never been a will located for Nicholas and it is safe to say, there never will be. Nevertheless he inevitably had one. Nicholas would have written his will back in Germany, before beginning such a daunting journey as sailing to America. But by now it is long lost. Yet it could have been recorded and there is always a chance that something about it may be located in the old Lancaster records. It would have been written in German which meant the English speaking official and scribe who was to record it would have not been able to read it. In a different language and written in old German-script, he would have had no idea what the will actually said. So the person presenting it would translate it and tell him what was in the will. The term given for this form of will is a Nuncupative Will, such as the excerpt below.

From the 1755 will of John Haag. Click to enlarge. To read a little more of the page, click here.

Compliments of FamilySearach.org.

"The Nuncupative Will of John Haag deceased being Wrote in the German Language

could not be recorded but thereon is Indorsed as follows Viz." sic

As to the guardianship, required for minors? As with the will, no guardianship papers have been located either. However we can assume that Hans would have taken the responsibility. Since in 1734, Andrew owned property and if you will, a plantation, we can imagine that the four children lived somewhat autonomously from their uncle. And even though Andrew was still a minor, he would have inevitably been charged with taking care of his siblings. He was after all, "the oldest" and he would have done it.

|

Regardless, there is always the off-chance, and it is certainly imaginable, the newly immigrated Bushong family, now sick with some dying, may have never involved the courts. Remember, they had just left Germany where their king and his government could not be trusted. Then consider that although they inevitably knew of William Penn, little about their new country would be known, its government, and for that matter, its people. In a brief time, it would all still be confusing and mysterious. Logically they would not know their countrymen well enough to trust them. So maybe with Andrew already in possession of his inheritance, Nicholas, now dying and possibly delirious, could have insisted Andrew keep quiet and not report anything? To this, the future run-ins with the Pennsylvania Militia further illustrate the possibility that Andrew never did see eye to eye with "the government." Andrew's uncle Hans would have gone along with his brother's death-bed wishes and helped, too. Still, it probably happened through the courts, with the papers lost or yet found.

As a final note, after their parents' passing, the four surviving children stayed until adulthood, in the Leacock and East Lampeter areas. Of them, three had children, and at last count, from Nicholas and Magdalena, this branch's progenitors, there are eleven descendant generations in the tree.27 Every one of them serves to further honor and validate the lives of these brave immigrant ancestors.

This Article is Copyright ©2020 by Rick Bushong and Commercial Use Prohibited.

Non-commercial use is permitted if copyright information is included.

References: Johann Nicholas Bushong

- The International Genealogical Index, (IGI), compliments of Familysearch.org, here

- Parish Records, Boltigen, and Oberwil i.S. Bern, Switzerland

- Compliments Dietmar Meyer, author, of the Reformed parish Waldfischbach Church Book transcriptions, email communications.

- German City Populations, viewable here

- Waldfischbach Church Records, Kaiserslautern District, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, search here

- Register zum 1. Kirchenbuch der Reformierten Pfarrei Waldfischbach (Holzlandkirchenbuch) 1684 - 1721. (Register for the 2nd church book of the Reformed parish Waldfischbach), published 1988, in Zweibrücken by the publisher Zweibrücker Association for Family Research, by Dietmar Meyer. Compliments of the author.

- Register zum 2. Kirchenbuch der Reformierten Pfarrei Waldfischbach (Holzlandkirchenbuch) 1721 - 1755 (1757). (Register for the 2nd church book of the Reformed parish Waldfischbach), published 1986, in Zweibrücken by the publisher Zweibrücker Association for Family Research, by Dietmar Meyer. Compliments of the author.

- A Collection of Upwards of Thirty Thousand Names of German, Swiss, Dutch, French and Other Immigrants in Pennsylvania, readable,

here.

- The Flow and the Composition of German Immigration to Philadelphia, 1727-1775 By: Marianne Wokeck Source: The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Jul., 1981), pages 249-278 viewable, here.

- Pennsylvania Gazette Oct 19 1732, Issue #203: The arrival of the Pink "John and William," page 2; read hear: page 2,

page 1

- Journey to Pennsylvania in the Year 1750 and Return to Germany in the Year 1754, By: Gottlieb Mittelberger :Published 1756, viewable, here.

- Pennsylvanian German Pioneers, A Publication of the Original Lists of Arrivals In the Port of Philadelphia

From 1727 to 1808, By Ralph Beaver Strassburger, LL.D., President of the Pennsylvania German Society, Edited by

William John Hinke, PH.D., D.D, In Three Volumes, Volume I. 1727 - 1775, Published 1934, pages 559 and 660, viewable, here.

- Bushong Bulletin Vol. 1, No 4. , page 2, by Judy Cassidy -Andreas Birshing listed on 200 acre Warrant of Land or Patent, adjoining Hans Busham of the county of Lancaster, near the Mill Creek. No.18. Another mentions Nipleys heirs, buy lands of Henry Strickler, containing 34 acres a part of the 200 acre tract of land of Andreas Bushoin.

- Statues at Large of Pennsylvania from 1682 to 1801 Volume IV 1724 to 1744, published 1897, page 329

- Abstracts From the Pennsylvania Gazette, editor Ben Franklin, 1728-1748, by Kenneth Scott, 1975, page 587. As published in the Bushong Bulletin Vol.1, No 4., page 2, by Judy Cassidy.

- The Origin of the Bushong-Boschung Surname, by Rick Bushong, published 2012, read it, here.

- Wikipedia: Conestoga Wagon, viewable, here.

- Pennsylvania Historic and Museum Commission A-19, page 373.

- The Charters of the Province of Pennsylvania and City of Philadelphia

and a Collection of Laws of Pennsylvania, Printed and Sold by B Franklin 1742.

- Wikipedia: Creasap's War, viewable here.

- Pennsylvania Gazette, November 2, 1732, view source;

full page.

- Pennsylvania Gazette, November 16, 1732,view source; full page

- Pennsylvania Gazette, November 23, 1732,here

- Pennsylvania Gazette, November 30, 1732,view source; full page 1; full page 2

- The Diffusion of Influenza: Patterns and Paradigms, by Gerald F. Pyle. Published 1986. Page 25, viewable, here.

- Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, by: Eric L Altschulerc and Aesha Jobanputra, published 2014, viewable. here.

- Bushong United Family Tree, search it, here.

- From Church Book, Dutch Reformed Church, Rotterdam, South Holland Province, Netherlands

- KNMI / Historic observations, weather station Utrecht

|

Bushong United is Copyright ©2021, 2023 by

Rick Bushong any Commercial Use is Prohibited.

Non-commercial use is allowed with permission or only if entire

copyright is included.

To Direct Search the Bushong United Family Tree

click here

|

|